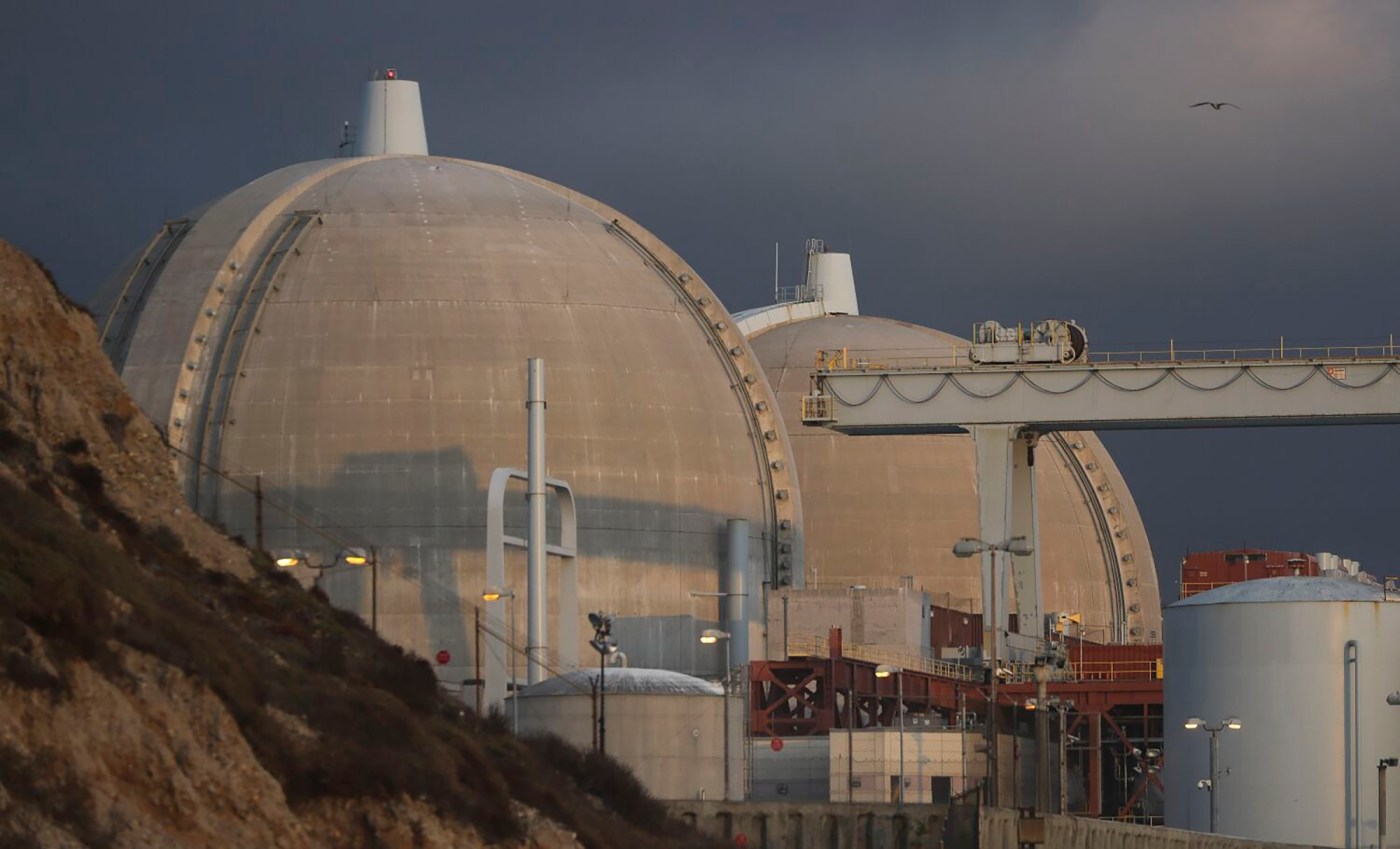

Irvine officials gathered Tuesday to confront a concern that has lingered on the county’s doorstep for more than a decade: What to do with the 3.6 million pounds of radioactive waste stored at the shuttered San Onofre Nuclear Generating Station.

Mayor Larry Agran convened a special City Council study session on Sept. 30 to examine how the decades-old waste — sealed in 123 stainless-steel canisters just 30 miles from the city’s borders — could affect Irvine and the rest of Orange County. He called on his city colleagues to consider a local “Plan B” to protect the region, including a study on whether Irvine could play a role in such an effort.

Any release of radioactive material, Agran warned, could impact millions of residents and thousands of businesses across Orange, San Diego and nearby counties.

“The spent nuclear fuel currently stored at San Onofre has regional implications for millions of Southern Californians, particularly residents of Orange County and San Diego County,” Agran wrote in a Sept. 15 memo announcing the meeting.

San Onofre, on the northern edge of Camp Pendleton, sits about 25 miles from Irvine and within 50 miles of nearly 8 million people, Agran said. The U.S. Department of Energy was tasked with creating a permanent repository for nuclear waste decades ago, but one has yet to be built. Current federal efforts, led by Rep. Mike Levin, D-San Juan Capistrano, propose consolidated interim storage sites in Texas or New Mexico, though Agran noted that the last of the fuel might not be moved until 2060.

“We need a local plan that once implemented, would safeguard us in Southern California for 100 years or more, even if no federal repository is forthcoming,” he said.

He suggested moving the canisters to higher ground on the inland side of Interstate 5 at Camp Pendleton. The fortified site, he said, would be better equipped to withstand floods, earthquakes, tsunamis or even potential terrorist attacks.

But “Plan B” is not intended to replace the long-promised federal nuclear waste repository. Rather, it would be a local measure prepared in anticipation of a national plan, which could take decades to implement, Agran noted.

“The facility would be designed to incorporate all manner of monitoring and maintenance to ensure the readiness of all stored nuclear waste for safe transport, if and when a national repository is finally approved, filled and operational,” he said.

No immediate decisions came out of Irvine’s Tuesday meeting, but the council is expected to revisit the matter at a regular meeting in November or December.

Gregory Jaczko, former chairman of the U.S. Nuclear Regulatory Commission, argued the waste cannot remain permanently at San Onofre.

“The site is not and never will be appropriate for permanent disposal,” he said, adding that the California Coastal Commission has only permitted the current site until 2035.

Jaczko pointed to Irvine’s history of environmental leadership, noting the 1989 City Council ordinance that banned chlorofluorocarbons (CFCs) in many industrial processes and consumer products. He said the city “can serve a similar role today by developing a concrete plan for removing the spent fuel from San Onofre.”

David Richardson, a professor of environmental and occupational health at UC Irvine, warned of the potential health risks if even a fraction of the material were released. He said an accidental release could double the leukemia risk for young children in Orange County.

But Southern California Edison, which operates the site, insisted the current storage system is secure.

“Safety is my No. 1 priority,” Frederic Bailly, the utility’s vice president of generation and chief nuclear officer, told city leaders and community members at Tuesday’s study session.

He said the containers exceed federal guidelines and are designed to resist corrosion in the marine environment.

“There is no credible scenario that could result in the release of radiological material beyond the site,” Bailly said. Pressed by Agran on whether that assessment would still hold decades from now, Bailly said it would.

Residents and activists who packed the council chambers in the early afternoon urged the city to push for action rather than waiting on the federal government. One speaker, who said she had lived near Japan’s Fukushima, urged relocation to higher ground from a site “vulnerable to corrosion.”

Others warned of environmental threats, stressing that “this is an Orange County and San Diego County problem” that requires local leadership.

“Irvine’s involvement on nuclear waste strengthens the broader push by local governments to get this waste out of our region,” Levin said. “Removing it will take cooperation at every level — federal, state, and local — and I’ll keep fighting in Congress for the federal resources needed to make it happen.”